One of the most fundamental questions in regards to how to apply training in triathletes concerns the widely accepted and implemented belief that training works best when it is “hard”. This is commonly expressed by the expression “no pain, no gain”. I was certainly raised in this belief and can still remember the wide spread admiration of both my teammates and coaches in my ability to push myself to the point of “puking” during swimming training sessions in high school during the 1970s. I carried this belief forward through some 20 years of my competitive athletics career until sometime in the late 1980s when the twin issues of both exercise induced bronchoconstriction and frequent overtraining became so chronic that they threatened to derail my ability to continue as an adult triathlete.

To really understand the question of whether or not we should strive to train “hard” a starting place is a discussion of what we mean by training intensity. Most athletes and coaches think of training intensity in terms of what they feel or experience during training. However that concept should more appropriately be thought of not as the intensity of the training but as the effort associated with creating/performing a given training intensity. More logically the training intensity is the actual rate of work being performed. In cycling for instance, riding at 200 watts (power and rate of work are the same thing) represents the training intensity of that ride. A heart rate of 140 or a perceived effort on the Rating of Perceived Effort (RPE) scale of 14 represent the effort, both physiological (heart rate) and perceptual (RPE rating), associated with performing that work intensity.

A second widely held belief associated with the “no pain, no gain” concept of training, is that the amount of effort we feel drives the outcome – harder efforts result in improved fitness outcomes or adaptation. This might be understood in the context of the widely held belief that failure sets in weight training result in more improvements in strength for instance because in forcing the muscle to fail we are somehow creating a “better” stimulus for adaptation. However this concept has been widely debunked by this 2016 meta-analysis and review https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-015-0451-3 which support the idea that in short term training programs using more controlled approach to weight training (basically sets not resulting in failure at the same weight or training intensity) creates the same performance gaining adaptations as an approach which employs the far more effortful failure approach to training. Further, a closer review of the long term studies (more than 12 weeks) reveals greater improvements in the controlled approach, although these differences do not turn out to be statistically significant in the meta analysis for the most part as such studies are few.

A practical interpretation of this is quite simply that training in a way which requires too much psychological effort and is also exhausting is far harder to carry out consistently then training which feels more comfortable and is not as exhausting. In short term research projects the “team’ effect and completion incentives will help offset this problem in the treatment groups using failure training for a time, allowing the failure groups to achieve similar results to the non-failure more controlled approach groups, but in the longer studies the failure group subjects begin to drop out more and or simply become overtrained. Anecdotally, in the real world of weight training a big day of your buddies pushing you to failure sets is probably one of the best predictors of future training program drop out.

A more involved question goes directly to the concept of whether the stimulus for performance improvement is a function of the volume and intensity (training load) of local muscle work performed alone or the physiological outcomes associated with it; such as the degree of acidity you experience or the level of oxygen uptake (VO2) achieved. The long term bias in the science of exercise physiology has been to focus on the physiological outcome side of the picture and develop training approaches which reflect the optimal stimulus for those outcomes versus strategies that maximize the amount of work performed at the targeted velocity or power without undue fatigue. This is expressed by concepts such as lactate threshold training, VO2max velocity training, lactate (really acidity) tolerance training and weight training to failure. Each of these approaches is based on the theory that using the training intensity and duration that produces the greatest degree of change in a fundamental physiological limiter to our ability to provide metabolic energy (such as the maximum amount of oxygen we can provide, acidity we can tolerate or lactate we can clear sustainably) becomes the best way to progress training adaptations to high levels. However, In practical application this means performing at the work intensity for as long as possible, which of course then results in both a large of degree of psychological discomfort during training as well as extremely high fatigue post training.

An alternate view of this concept is that the more important stimulus is the cumulative work performed at a given work intensity, regardless of the level of oxygen transport, acidity or lactate clearance achieved. In the weight training realm this might be expressed as follows. If a given athlete could squat a 1 repetition maximum (RM) of 200 pounds, he might then perform failure sets at 85% of that 1 RM at 160 pounds. Typically this would result in about 5-8 reps in the first set to achieve failure with subsequent sets almost always falling off in the number of repetitions completed prior to failing. Rarely would more than 3 sets be completed. Such training is very demanding psychologically, requires longish rest periods between sets of several minutes or more to complete and is very fatiguing. Those who have engaged in such a training approach over time of time also know how much mental effort is required just to begin each training session as well.

In a more controlled approach to training the same athlete might simply do lower repetition sets (-2 reps from failure ideally) at the same training intensity (weight of 160 lbs.). In so doing each set is relatively easy to complete as acidity and central nervous system fatigue is greatly reduced, rest periods are greatly reduced (often to around a minute or less in my experience) and a far greater number of sets can be performed, typically meaning the total volume of training at this training intensity (160 lbs) can be increased. At a minimum, the previously mentioned research suggests this approach will allow for the same gains in strength/power/muscle mass while training in a way which can more easily be perceived as enjoyable. Over time the improved training consistency associated with this approach is likely to result in a greater net gains in strength, power, hypertrophy, etc..

This concept has not been directly addressed in the endurance portion of the training continuum. However, one study looking at the best training protocols to improve VO2max using the velocity of running at VO2max (VVO2) indirectly illustrates the same idea. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-003-0806-6 This study used the concept of adding twice weekly interval training in two treatment groups of moderately trained runners at differing percentages of the time limit over which the velocity at VO2max can be maintained in a given athlete; with a third control group continuing to train normally. A higher percentage of time limit meant the athlete ran longer at the target intensity in each interval , likely then experiencing more acidity and discomfort during each effort as well as spending a greater time during the interval at VO2max. The first treatment groups training protocol used six intervals run for a duration of 60% of that athletes time limit at VO2max velocity once weekly . The second treatment group ran five longer intervals for a duration of 70% of time limit at VO2max. While these differences seem small, they are critical; just as the last few repetitions in a weight training set approaching failure are critical to determining just how hard that effort feels , how much fatigue the effort will create, and how much rest will be needed prior to recovering for the next work set or interval effort. The rest of their weekly training was controlled aerobic running and not progressed. In both cases the athletes were not running until complete exhaustion at 100% of time limit at VO2max velocity meaning the interval sessions were hard but doable – think about how you might feel about lap three of a 1600 meter time trial at your best effort. In addition, the amount of time spent running at VO2max velocity (not maximal oxygen uptake) was equated by using fewer interval repetitions in the group doing the longer intervals. Conventionally, we would then expect a better training response to come from the longer interval training set group, whereby more time was logically spent at VO2max. However, the shorter interval group was the only group to improve significantly in a 3000 meter time trial (17 secs versus 6 secs in the other treatment group and no change in the control group) suggesting that the need for increased oxygen uptake and discomfort was probably secondary to the amount of running actually done at the target velocity and the ability to adapt more readily to the less intense interval training session. Basically what this study suggests is that a more doable training approach (shorter, less discomfort inducing intervals at the same relative velocity) results in better adaptation to high intensity interval training than an approach which is more likely to create more exposure to the physiological stimulus but is also more difficult to do. Further, Veronique Billat, the most heavily invested researcher on the topic of training at the minimal velocity at which VO2max is achieved, demonstrated in a classic training study using intervals at 50% of the time limit to VO2max at that velocity that such an approach can be implemented to great effect and without creating overtraining. https://europepmc.org/article/med/9927024

Anecdotally I became fully convinced of the utility of using this concept (focusing on work achieved at the target intensity in relative comfort versus maximizing physiological stimulus) during my coaching use of supplemental oxygen in creating a high/low training model for the athletes I coached for many years in Colorado Springs at the Olympic Training Center (picture on this websites home page). In particular, Hunter Kemper successfully progressed from running approximately a 5:10 minute per mile pace to running a 4:35 minute per mile pace during 4 minute intervals over several years by breathing a 50% oxygen concentration mixture, which changed his expected RPE during such efforts from 15 -17 down to typical RPEs of 12 or less . Essentially this approach decoupled his normal sense of effort and associated acidity and heart rate from the actual work intensity he was performing in training, yet it still translated to progressive improvements in 10 kilometer triathlon running until he eventually became one of the fastest triathlon runners in the world. Of course he not only tolerated these sessions well but actually looked forward to them.

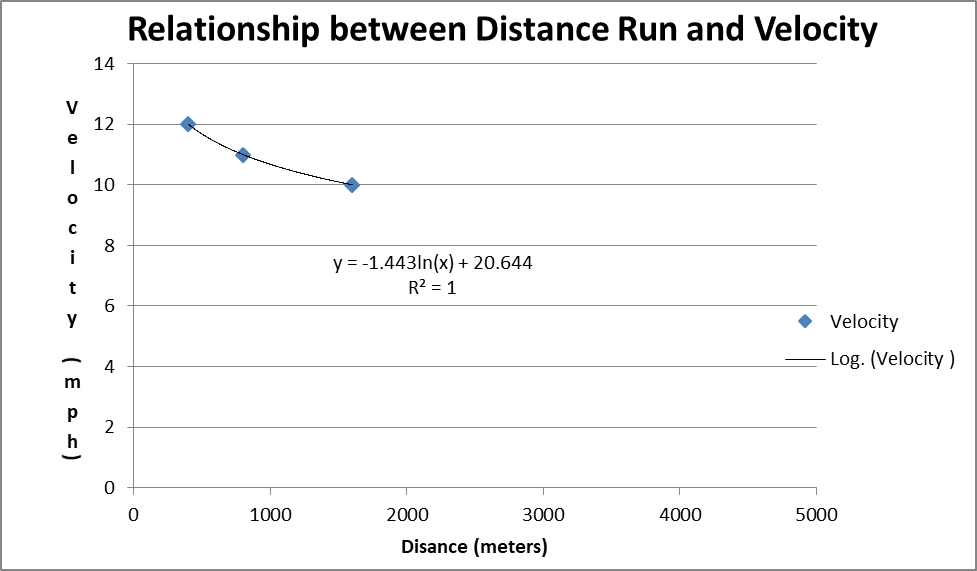

Of course the rest of us in the real world can’t afford to train with supplemental oxygen , so how can we practically implement the concept of training at progressively higher work rates but always at reasonable perceptions of effort? The simple answer is to employ interval training using only intensities and durations that represent your current ability, versus trying to train as hard as you can in any given context. For instance, if my current ability allows me to run a mile time trial in 6 minutes, when I want to train to improve that specific performance ability (which relates quite closely to VO2max velocity) , I would then design an interval set to be run only slightly faster than my current ability with intervals short enough to be relatively comfortable to perform. Here I suggest two rules. First, only work slightly faster (less than2%) than your current ability. For a 6 minute miler that might mean running at a 5:52 pace. Second, break the work up into at least 4 intervals. For example, to train for a 1600 meter effort, run intervals of 400 meters or less, in this example at a 1:28. Such intervals will be relatively comfortable and allow you to accumulate time at the desired training intensity without undue fatigue, creating a platform for successful adaptation. I have long referred to this concept with the axiom “the point of training is not to train hard, but to train so that you can do harder work”. Of course this applies in both swimming and cycling as well. The only real trick is to have valid idea of how fast you can perform at a given distance, which is normally established through either through time trials or racing, as most of us do not have the time or expertise to translate data from physiological tests. However, there are also reasonably accurate, particularly in experienced athletes, methods to predict current performance ability at longer distances using shorter distance tests and then applying a logarithmic function in something like Excel. I initially presented this approach in Championship Triathlon Training in 2005. It can be understood by considering the following sample graph created in excel.

Figure 1 -Running Distance (X) and Velocity (Y)

In this athlete who ran 400 meters in 1:15 (12 mph) and 800 meters in 2:43 (10.99 mph) he would be predicted to run 1600 meters in 6:00 (9.99 mph). To determine his 5000 meter pace (or any longer distance pace) we would then just use the log function and insert the distance as x to get the mph as Y.

So for instance -1.443 * (LN 5000) + 20.664 = 8.35 mph or a 5000 meter time of 22:18. This athlete is reducing his velocity 8-9% each time he doubles distance, a concept I refer to as his fatigue rate. The fatigue rate lowers as we adapt successfully to greater volumes of training reaching 4-6% in elite triathletes (based on my past coaching and testing) and even 2% in world endurance running record holders, such as those who have held the 5K and 10 K world records simultaneously. It is more typically 15% in typical college athletes (I have measured many hundreds) and as high as 25% in more sedentary people (some of my students are sedentary). This variation is why it is so important to measure at least two distances and not just apply the standard tables which are largely based on trained collegiate distance runners with fatigue rates of 6-7%.

Once a reasonable target training intensity for a given distance is established, then one can apply the rule of at least 4 parts to develop a training set (more as the intended distance increases) . When implementing such a set the point is to replicate the desired intensity (even when that feels too easy 😉 and not try to improve upon it. In running, for instance, this done in the easiest manner by using a treadmill (where pace can be controlled externally). However the same can be achieved using power, GPS or even the time honored stop watch and measured distances. Lastly, the concept is applicable to any distance of training and builds on the well established principle that intervalized training is our most effective tool for making training progressions to become the idea that “controlled” interval training is more effective than “unrestrained” interval training.